Chaos in Healing

- Gina Greenlee, Author

- Jul 20

- 4 min read

The vestiges of childhood crises led me to art making and play as accessible forms of chaos. I recognized, if I could use chaos as a portal into creating art, I also could use it as a conduit to create my life. Perhaps, such chaos could also further my emotional healing.

Not a tidy process.

Early in therapy, my psychologist repeatedly told me that children from dysfunctional families such as mine imagine we have more power over people than we do. We believe if we act according to a template, then people will respond in a predictable way. Of course, this isn’t true. However, children in dysfunctional homes think it’s true because it was the only way to emotionally survive.

If, as a child, I felt that I had no control over my crazy home life, then I would have fallen into hopelessness and despair. So, I created multiple systems to manage the chaos. Compartmentalization was among them.

Wringing Sense of the Nonsensical

Psychologists define compartmentalization as a defense mechanism that humans use to avoid anxiety that arises from the clash of contradictory values or emotions. Survivors of childhood family dysfunction compartmentalize their thinking to survive that clash.

One way we do that is with black-and-white (either/or) thinking. This person or situation fits this category. It’s the child’s attempt to employ a template to wring sense from a nonsensical situation.

As children, we suspect it when adults don’t take responsibility for their behavior even though we don’t fully understand why. So, we attempt to exert some control over what, in reality, is uncontrollable.

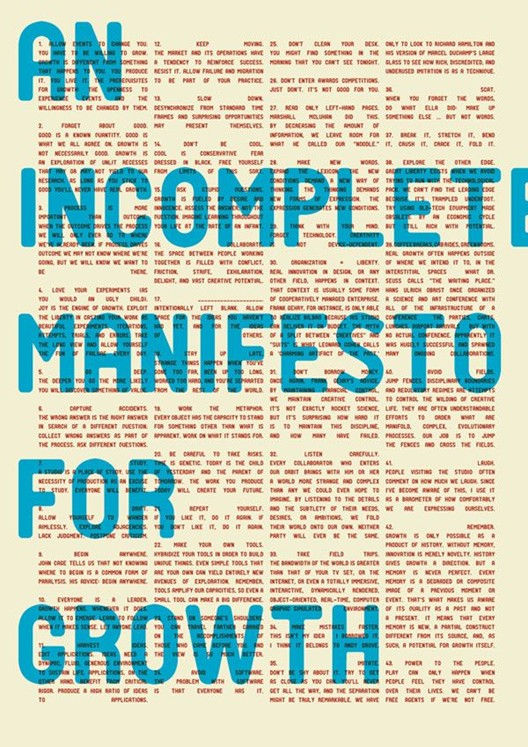

Image Credit, Edward Lear, author of

The Book of Nonsense on Pixabay uploaded by Prawny

Black-and-White (Either/Or) Templates

My compartmentalized templates seemed to “work” while I was growing up because shades-of-grey are not recognizable or tolerable in chaotic childhoods. For me, these habitual defense mechanisms carried into adulthood.

However, psychotherapy helped me to recognize the cost of those adaptations: what grounded me in childhood is maladaptive in adulthood.

With professional help I began the journey of shifting these patterns.

Part of the chaos in healing happens when evolving from a compartmentalized life (extremes) to an integrated life (continuum).

This transition toward integrated living can feel overwhelming and disorienting because it involves significant changes to established patterns and routines.

Shades of Grey

But that unsettling feeling of being out of control is productive. It marks the collision of ideas and habits forming to create space for something new. When you migrate from compartmentalization to integration, you

intentionally blur the lines between distinct aspects of your life previously kept separate to feel in control. You do this by restructuring your time and energy.

A Brief Playbook: Transitioning from Compartmentalizing to Integration

The transition for me began with experiments that started with this question: What if?

What if I wrote books in places other than in my apartment office? I asked this question because in my body the experience felt like me at the office during my corporate day job – uncomfortable seating weighted with deadlines. And that stilted energy crept into my writing.

So, I explored writing in bed, reclined and propped up with pillows.

I wrote on the beach, in restaurants, standing online at the post office and at the bank.

Of my visual artmaking, I asked, what if I let go of the need to rent a separate art studio in a separate building or different part of town? The answer: make art at home in a designated space. A good starting place. Over time, though, it felt constrictive. Project ideas were cropping up at all hours when I was engaged in other activities. I’d see something in my living room or kitchen that would prompt an idea for a project. As quickly as the idea came I knew it could float away.

To act on art ideas in real time, I needed to create right where I stood or sat. This was the beginning of me establishing different artmaking spaces throughout my apartment instead of confining my creative space to a single area. With that awareness I placed art supplies and artmaking tools in different sections of my home: bedside, kitchen counter, living room floor.

I viewed ephemera (groceries labels, office supply packaging, mail circulars) as art supplies, not trash.

More and more, everything in my environment became fodder for art making. Acting on creative ideas in real time felt good. No matter what else happened throughout the day, I had shown up for myself.

That good feeling affirmed the journey of integrating my previously compartmentalized life.

Once the lines between work and play, “job” and “leisure” were no longer sharply drawn (compartmentalized), organic collision of ideas gave rise to new projects.

In the realm of artmaking, instead of judging my studio as “messy,” I recognized that I could intentionally collide disparate elements to advance discovery.

This artistic practice of intentional collision (integration) transposed itself onto daily life: I felt less anxious and increasingly comfortable with disparate compartments of my life coalescing into an integrated whole.

My comfort with intentional collision of ideas lead to heightened curiosity and playfulness about artmaking all the time in real time. I created mobile art studio kits that contained markers, sketch pads, scissors, tape and glue. This allowed me to doodle, collage, and capture ideas wherever I went. While on breaks during my day job, I unzipped my travel art studio and created paper dolls, collages and handmade books – always a project-in-process in my tote bag, so I could be ready to engage new toys as they emerged.

A transformation was underway: from feeling anxious, out of control and overwhelmed by chaos to intentionally cultivating chaos as an experiment in curiosity. (What if?)

Curiosity felt like play – a feeling I carry with me wherever I go; not only in a tote bag but as a way of being in the world.